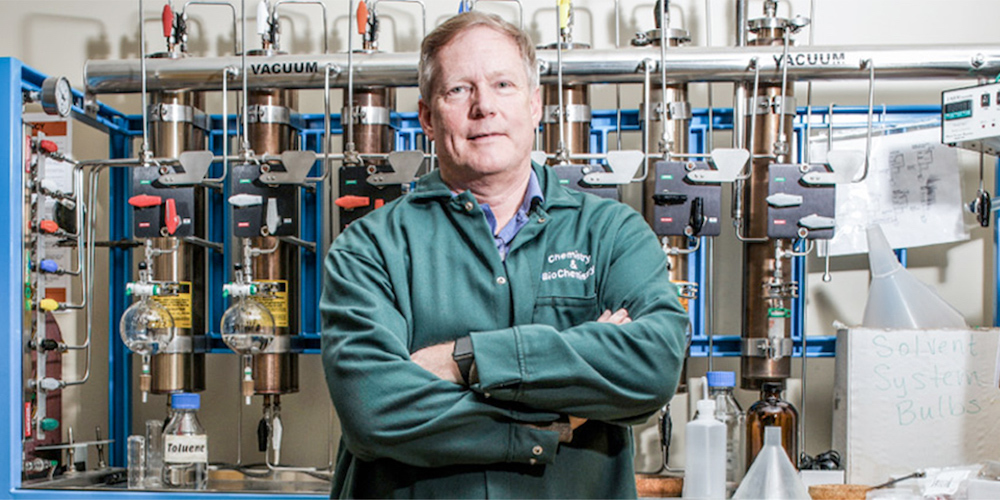

John Wood

Mentorship is a driving force for John Wood in research that could eventually lead to cancer drugs. Wood serves as the Robert A. Welch Distinguished Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry and Co-Director of the Baylor Synthesis & Drug-Lead Discovery Lab. Since coming to Baylor in 2013 after serving at Yale and Colorado State, he has continued to build a nationally recognized research portfolio while focusing on the next generation of researchers who come through his laboratory.

Transcript

DEREK SMITH:

Hello and welcome to Baylor Connections, a conversation series with the people shaping our future. Each week we go in depth with Baylor leaders, professors, and more discussing important topics in higher education, research, and student life. I'm Derek Smith, and today we are visiting with John Wood. Dr. Wood is the Robert A. Welch Distinguished Professor and Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas Scholar for the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, and Director of the Wood Research Group. His research focuses on developing chemical census of naturally occurring molecules that possess medicinal properties. Wood came to Baylor in 2013 after serving as a faculty member at Yale University for 13 years and for seven years at Colorado State. A lot of great things have happened here since he joined the University, and we'll talk about some of that and more on the program ahead. Dr. Wood, really great to have you on the show. Thanks for joining us today.

JOHN WOOD:

Thanks for having me today, Derek.

DEREK SMITH:

Well, we'll get a dive into what it is that you do and what it means, but let's first, get a picture of what your work world looks like. If we were to just visit your lab, if there's such a thing as a normal day, what sorts of things might we see taking place?

JOHN WOOD:

Well, if you were to walk into the lab right now, for example, there'd be 13 students, maybe 14 students working in the lab. Some of them, one of them are post doc, most of them are graduate students and two or three undergraduates, typically. Everybody in the lab has their own project that they're working on except for the undergraduates, they work in conjunction with a graduate student. And every day those graduate students will be doing a new chemical reaction, typically. Something that they've not done before, and different aspects of that work involve purifying, whatever they may be starting that reaction with, running the reaction itself, purifying or isolating the products at the end, and determining what happened. Then in addition to that, in the laboratory, in addition to the laboratory itself, there's a office area. So students will be working on writing a manuscript, perhaps for a publication, or working on a grant proposal of some type, or a presentation that they might be giving that week at group meeting. Or every week they have to write a report to give to me, so they'll be working on those as well.

DEREK SMITH:

When you say a project and you mentioned reactions and things of that nature. What kinds of projects might they be doing?

JOHN WOOD:

So our lab focuses on the census of small molecules, and so each student has a different molecule that they're working to try to develop a census of.

DEREK SMITH:

So I gave a little 30 second version at the beginning of the show of what you do. Could you unpack that a little bit more? Like if you were talking to someone, say at church, and they said, "Well, what do you do?" How would you describe that?

JOHN WOOD:

I would say that if I wanted to relate that to somebody that was completely foreign with what would be going on in our lab or unfamiliar with what's going on in our laboratory, I would say I'm training the students to be very sophisticated pastry chefs.

DEREK SMITH:

Okay.

JOHN WOOD:

Okay. So what we're trying to make, instead of making a cake, or a Kouign-amann or something like that, we're trying to put together a small molecule and we'll go through the steps one step at a time. The same way, if I were going to be making a pastry, I might be making the dough, I might be making the butter brick, I'll be layering the dough and the butter together is different steps along the way to eventually come with this end product that I'm trying to make. In cooking you can analyze whether or not your reactions worked by tasting that end product and seeing whether you enjoy what you've just made. In the laboratory we'll look with using instruments, different instruments in the chemistry department that we have, to see whether or not what we've just done has worked the way we'd like it to.

DEREK SMITH:

What kinds of molecules are these? Do they come from products or how can we picture those?

JOHN WOOD:

Sure. All the molecules that we work on, people would call it natural products. So these are molecules that have been isolated from some source in nature, whether it's a sponge in the ocean, whether it's comes from a bacteria in the soil that's been producing this molecule. Or one of the compounds, for example, that we made was found in a fungus that was growing on a juniper bush in Dripping Springs, Texas.

DEREK SMITH:

Wow.

JOHN WOOD:

So that's, they're all natural products. Small molecules.

DEREK SMITH:

I'm visiting with John Wood from Baylor Chemistry and Biochemistry and Dr. Wood, so if in baking a great cake or whatever is the end product, what's the end product from your lab to the next step?

JOHN WOOD:

The end product in our laboratory is an exact reproduction or replica of what nature has made in the plant, or the microorganism, or wherever this compound has been isolated from. Where we go with it from there is typically, that's probably where most of the projects, the vast majority, 99% of the projects end. We don't explore them further. These compounds, you could ask, "Well, what drove somebody to isolate this compound from nature in the first place? Why?" And typically, there'll be people who will be studying plants. They'll extract those plants and explore those extracts to see if they have an interesting biological property. And if it does, then they'll take the time to isolate what's responsible for that biological property in the plant. And typically it's a small molecule of the tech will prepare. And so the compounds that we're preparing do have interesting biological properties, but our focus in our laboratory is really just the training of students on how to put these molecules together, not so much on the biological end properties of these compounds.

DEREK SMITH:

I know at the beginning we talked about the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas. CPRIT funding has been a big part of what you do. So if people are thinking about a cancer therapeutic down the line, I guess you're very, very early in that process.

JOHN WOOD:

Sure. Our process, if you're going to be developing a therapeutic in a company where you'd actually like to develop a drug for the treatment of cancer, you would have chemists working in your company who you are called medicinal chemists. They're exploring, looking for new small molecules that might have the type of activity that they would hope to see in an anti-cancer drug. And then you would have also in those companies, chemists, who would ultimately be responsible for manufacturing those compounds on a larger scale, making enough to be put into pills, or whatever, however this drug is going to be administered, but making enough of that material to do the assessment of safety or to go ahead and go forward with the drug. The chemists in my laboratory, the chemistry that they're learning, the students, what they're learning could be applied at either phase in that process at the very beginning in the discovery phase or in the very end, the manufacturing phase. And so they're learning all aspects of that chemistry in the laboratory. We don't necessarily apply it at the end. It's really the learning that we stop when the learning, when a student has learned how to put these molecules together.

DEREK SMITH:

We are visiting with Dr. John Wood and Dr. Wood, I want to ask you about your students and mentorship here in just a little bit, but also want to zoom out and ask you about what brought you to Baylor. You've been here at Baylor through some eventful times for the University of growth in research and towards R1. So I'm curious, 2013, you came to Baylor. What was it that brought you here?

JOHN WOOD:

Well, I had come to Baylor in 2012 or 2011, somewhere in that timeframe at the invitation of Chuck Garner, who used to be on the faculty here at the chemistry department at Baylor. Chuck turned out to be my mentor as an undergraduate at the University of Colorado, and he'd invited me down to give a seminar, and I'd never been to Baylor before. I knew a little bit about Baylor, but not much. My expectations were to find a small liberal arts college in the center of Texas. But when I arrived, the Baylor Sciences Building was here. It was a much more, bigger operation than I thought it was going to be at the time. And so I was surprised by that. And then after giving the seminar, I had gone back to Fort Collins, that's where Colorado State University is. And a few weeks later, Chuck had called on the phone and told me that they had this Welch Chair position at Baylor. The faculty had enjoyed my seminar. They were curious whether or not I would be interested in a position at Baylor. And I'd have to say that had I not come down for that visit, my initial response would've been, "No, I'm happy. I'm happy where I am." But I saw a considerable potential when I was here during that seminar visit and so I came back and explored this opportunity as being the Welch Chair at Baylor, and then went forward with the interview process and applied eventually for the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas. They have a recruitment of established investigators grant that provides considerable more funding when you come to the, if you were to accept the job. And that grant came through. And so I'm like, "Okay, this looks good."

DEREK SMITH:

Is that a pretty good competitive advantage for Texas and for universities in Texas when you've got CPRIT or the Welch Foundation or things of that nature?

JOHN WOOD:

Yes, it's an excellent advantage. Not only an advantage for recruiting young new faculty, they have programs for that. They have programs for recruiting established investigators, plus they just have grant programs that researchers can apply for. And so all of those are limited to people doing research in Texas, and so it's definitely an advantage.

DEREK SMITH:

You know, mentioned you saw a lot of potential at Baylor, and the BSB had been up and running for about a decade at that point, but we're still a few years away from things like R1. It's one thing to have vision, I suppose it's another thing to pull it off. What made you confident that Baylor could reach some of those goals?

JOHN WOOD:

Well, at the time that I arrived, I'd already seen how things were working at Yale for many years. And then I saw how things were working at CSU and in my brief visits here, I could see a little of a glimpse of how committed people were to the notion of growing the research enterprise here. It was, when I visited in the interview process, I think it was where we were, my family had come down with me. We were given a tour of Baylor in the athletic facilities, and we'd known that Baylor had a strategic plan where they wanted to grow their research enterprise, but also they wanted to improve their R1 athletics. But they'd built the BSB before they built McLane Stadium. And so in my mind, the priorities were right. Sorry, Coach Aranda, but you know...

DEREK SMITH:

He might actually agree with you. He might. Yeah.

JOHN WOOD:

So that was good. So when I talk about potential, you have the facilities, you had pretty good instrumentation, space to grow, and definitely the commitment in the administration to do that. And so those were definitely attractions.

DEREK SMITH:

In higher ed obviously, like with Coach Aranda, McLane Stadium, he takes a student athlete there in high school, they're going to be impressed or maybe coach that he wants to join a staff or whatever. As a faculty member, how can we envision how the BSB stacks up in that world? I think we can a lot of the senior sports fans can picture a lot of the different stadiums or basketball arenas, but how does the BSB compare?

JOHN WOOD:

The BSB is excellence, the best facility that I've ever worked in my career. Instrumentation here is better, more accessible than I've had access to before. And so it's made the recruiting of students easier. It's also made the recruiting of faculty easier, having that in place. We were able to, through the auspices of the CPRIT grant, build out instrumentation that was needed for my research, but instrumentation that could be shared and be attractive to new faculty members that would want to come to Baylor and start their research program or continue their research programs. We were able to recruit Daniel Romo, for example, from Texas M and M, I think largely due to the facilities that we had put in place. And also then after not only just having the facilities, the next phase after I arrived was to begin to try to attract students that were going to be excellent graduate students and be able to go on to good places. And also demonstrate that the students that were in my group could be placed into good positions. And so once you've demonstrated that you can succeed here, not only in terms of attracting good graduate students, in terms of doing good work, in publishing good papers, bringing in grant money then it's a little bit easier to attract other faculty to that situation.

DEREK SMITH:

This is Baylor Connections. We are visiting with Dr. John Wood, the Robert A. Welch Distinguished Professor and Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas Scholar for Baylor's Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry. And you mentioned attracting students, Dr. Woods. Let's talk about your lab group and certainly now and over the years, we were pleased to have you in Baylor Marketing be a part of our R1 campaign that launched last week. And when we visited with you, I asked you some questions, thinking maybe we'll talk a lot about the chemistry, the science, the cancer prevention, and you did. But what really seemed to make you come alive was talking about your students. So let's talk about that. First off, just broadly, what do you enjoy most about the lab group experience, the professor, other scientists, postdocs, and students?

JOHN WOOD:

Well, the lab group experience is that you're dealing with a constant group of people who are young and enthusiastic about where they are. Teaching is enjoyable. Teaching large classes of students is fun. I enjoy that. But not everybody in my organic chemistry class, sophomore organic chemistry classes, interested in organic chemistry, and they shouldn't be. They're here to explore the things and find the things that they're interested in and not interested in. But most everybody that comes into the lab group is interested. They want to be there, they want to learn, and they're eager. And so that's a very fun situation to be in when you have a very captive group of students that you can work with, and you get to work closely with them for a number of years. I'm in the lab daily, speak with everybody daily, and you end up spending lots of time with these students, and they eventually become just like an extension of your family. And it's a very close relationship that's developed. And that's I think the most enjoyable aspect of the job is just being able to constantly develop great relationships with really, really talented people.

DEREK SMITH:

For you personally, what does mentorship mean? What does mentorship mean in the context of who you're with on a daily basis?

JOHN WOOD:

Well, to me, mentorship means I'm trying to provide an opportunity for the students in the laboratory. Generating an environment in which that they can thrive, and also an environment in which they can learn the subject that were, the skills and develop the skill set that I want to see them develop in the course of their PhD. So it's really, mentorship to me is providing an opportunity and supporting the students through this learning process. It's not just teaching them the subject, but it's overseeing the whole development of them as they go through the PhD.

DEREK SMITH:

When you're thinking about, you talked about the fact that you create these molecules and 99% of them hit a wall fair fairly early in the process. And certainly when you're thinking about cancer, it's a long game. It's a very, very long game. And you're training students to play a role in that. What is it that, is it, I want to say hard? Obviously you all enjoy it. Is it hard to stay motivated? How do you break that down into the bite sized aspects that keep the carrot and the stick and the goals in front of you?

JOHN WOOD:

Well, the drive, I think, to do that, and in the long term, I think you can sum that up just by saying conquering the unknown would be what drives you. And the students in the laboratory, they get to conquer the unknown almost on a daily basis. Every day when they come to the lab, they're going to set up an experiment and they don't know whether that's going to work or do what it is they would hope that it does. And so that's an unknown. By the end of the day, they know that they've been able to achieve this thing that at the beginning of the day, they were uncertain about. Most of the time, I mean, 90% of the time, the things that they try fail. And so they have to deal with that a little bit. But there's enough of the success in sprinkled in and dealing with discovering something that was not known before that provides enough satisfaction to get by that. A certain percentage of the time, a smaller percentage of the time, five or 8% of the time, they may do an experiment and it works the way they want it to do. That's very gratifying. And then the very small percentage of the time, they'll do an experiment where something completely unexpected happened, and so they'll discover something new at that point. And so it's really every day coming into the laboratory, you don't know what's going to happen. And hopefully by the end of the day, it's been a learning experience in some fashion or the other.

DEREK SMITH:

Dr. Wood, earlier I asked you talk with the cake and bakery analogy. What's the end goal final finished product? I mean, I want to put words in your mouth, but almost sounds like what you're really saying, and it's the students that you're passing the baton to that are the finished product. Is that the case?

JOHN WOOD:

Yeah, absolutely. Yeah. One of the biggest questions that a student will have when they're starting their graduate career is, how do you know when it's time to get the PhD? Or how do you know, when is it going to be time for me to get my degree? And my answer is always, "My goal is for people that leave my laboratory to be equipped with the skills to look at a molecule, design a census of that molecule, and go into the laboratory and put that census into practice." And the reality is that most people can develop that skillset within about a year or two. And so why does it take four years to get the PhD then? And the other answer, part of the answer to the question that I give is that in addition to developing that skillset, you need to have a good story to tell. And a good story is a story that's filled with failure. You've tried to do something and you've failed, but you've conquered the unknown, you figured out what happened, you've taken what you've learned, and you've solved that problem. And then you go on to the next step and you've failed. You learned what happened, you conquered that problem, and go on. So it doesn't really matter whether they finished the project that they're working on per se, at the end of the day, they can give a job talk where they've met failure and gotten over it, met failure and gotten over it. They've become people that subliminally in their job talk, they're problem solvers, and that's what the world needs, and that's what people want to hire. And so as soon as I have somebody that has the skill set and has established problem solver, they don't get discouraged, they're ready to go.

DEREK SMITH:

That's great. Visiting with Dr. Wood and Dr. Wood, you said all of your students must have a hobby. Is that hard to enforce or tell me a little bit about why that's such a key value?

JOHN WOOD:

Well, I don't think that it's hard to enforce, but in our laboratory, as I kind of indicated a little earlier, everybody has their own project. And that can be a very difficult environment to work in it. You can be fairly isolated. There'll be moments in the day when, or many moments in time, months maybe where your project is not working, but the person next to you, they're succeeding. And so this is a very difficult situation to be in. And just to maintain a healthy, good mental health, I think it's important for the students to step out of that situation that they're in, where they're judging themselves is not good as their neighbor, or they're worried about whether I'm judging how well their chemistry is doing, but to step into the hobby that they have where they can be away from everybody else, succeed at their own pace, and do something that's gratifying to them, I think is a very important thing for them to do. And it's also, I think and important for me to tell them that it's okay to do that. They don't just have to do chemistry all the time. It's important for me to have them go out and do other things. And the reality is that in my own experience, if I'm pursuing my own hobbies, for example, there'll be many times when I'm doing something different and then the thought will occur to me, "Oh, what the way we should solve this problem in the lab is this." And so oftentimes when you let your mind move away from the problem, the solutions will come to the surface. And so I think the students also benefit from that too.

DEREK SMITH:

Well, I know you model that. Your lab website has a list of your hobbies. What are some ways that you are able to withdraw a little bit and pursue some passions?

JOHN WOOD:

Well, it depends on where I am. We still maintain a home in Colorado. That's where my woodworking shop is. So if I'm in Colorado, I can do woodworking. If I'm in Texas, it's cooking typically nowadays. Those would be my two main hobbies. I think also in more recent times there have been small things like learning how to do screen printing on shirts or learning how to do sand blasting to etch glass. And so we'll do gifts for the students when they finish a project, we'll make a shirt for them or sandblast the image of the molecule that they've made onto a glass or print it on the back of their shirt and things like that. So it's small hobbies like that.

DEREK SMITH:

That's pretty cool.

JOHN WOOD:

I have a shirt for you here by the way.

DEREK SMITH:

Oh, well, thank you. Wow. Let's see here. Oh, this is, wow. The Wood Group.

JOHN WOOD:

Yep.

DEREK SMITH:

Let's see. Oh, very cool. So it's got a lot of molecule designs on the back and a bear. What's the bear say on it there?

JOHN WOOD:

It says W6, but we had had a contest for a logo for the group at one time, and one of the students desperately wanted it to be WG for the Wood Group, and his G'S looked like a six.

DEREK SMITH:

Oh.

JOHN WOOD:

o we made it into a six and it just stuck. So it's W6.

DEREK SMITH:

Very cool.

JOHN WOOD:

It should be Wood Group, but...

DEREK SMITH:

Thank you. I appreciate this. Yeah, this is a first on the program, so I appreciate that. Thank you. And...

JOHN WOOD:

Made with my own hands.

DEREK SMITH:

Very cool. Yeah. Well, you got another business model if you ever decided you wanted that. So with this, you've got these hobbies, these students. Let me ask you, I'm curious. So if your students have to have hobbies. Have you ever had a student who had a hobby that particularly intrigued you, either made you want try it, or just fascinated you that they were interested in?

JOHN WOOD:

Well, I mean I've had some, I can't say yes to that question. There are students that have hobbies, whether they're, some of them will play musical instruments, and I can wish that I could play the instrument the way they play the instrument. Or one of my recent Baylor PhDs was, she's a very good artist and I just wish, I've always wished that I could draw or do art the way she's capable of doing it. She designed the bear on the back of the shirt there.

DEREK SMITH:

Oh, cool.

JOHN WOOD:

So those are things that I wish that I could do. I have never tried to do them, but...

DEREK SMITH:

Yes you, it sounds like you find you're probably even more intrigued by, more impressed by who they are as a whole person or the skills that they bring. That's pretty neat.

JOHN WOOD:

Right.

DEREK SMITH:

Maybe a talent show some days in the offer, we have a reunion, everybody bring their talent. I don't know. I could picture something like that.

JOHN WOOD:

Right.

DEREK SMITH:

Well, we are visiting with Dr. John Wood and Dr. Wood, as we head into the final moments of the program, I'm curious. Looking ahead here for you, you've painted a great picture of what the day to day is like. Looking ahead, are there any elements within your group or what's happening at Baylor, any direction really that has you particularly excited going forward? Or is it just pursuing those things we've talked about?

JOHN WOOD:

Well, I think continuing to pursue the things that we've talked about so far, I'm really looking forward to. There are a couple projects that we have going on in the group that I'm, molecules that we're trying to make that I think are really cool compounds. They have some great biological activity. So being able to put those together and maybe explore some of that activity is an exciting thing. Seeing Baylor achieve R1 in rapid fashion and seeing how that evolves or continues to evolve, I think is an exciting thing to look forward to. It was, as you move from institutions like Yale to CSU or from CSU to Baylor, your colleagues in the profession kind of give you a little bit of an odd look. What were you thinking when you did that? So there's a little bit of very good gratification there to, they can understand now that it was why you would do and want to be part of something like that. And seeing where that's going to continue to go is going to be something that's interesting. And in terms of hobbies, I have the next hobby's going to be learning how to make bamboo fly rods. And because I'm not getting any younger and I don't necessarily want to spend my twilight years in my office in the BSB, I'd rather be walking the streams in Colorado and Montana fly fishing with my own...

DEREK SMITH:

Nice.

JOHN WOOD:

...rods and flies that I've made. So those hobbies are in the early stages of development.

DEREK SMITH:

That's cool. We'll have to check out your website to see when those are ready. When you decide they're ready for prime time. They're on the website. Well, that's great. Well, we hope you get some time to enjoy those, but the not too soon we like having to here, so that's great. Well, thank you very much. Dr. John Wood, our guest today on Baylor Connections. Dr. Wood serves as the Robert A. Welch Distinguished Professor and Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas Scholar for Baylor's, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry. Thanks so much for joining us.

JOHN WOOD:

Thank you, Derek.

DEREK SMITH:

I'm Derek Smith, reminding you you can hear this and other programs online at baylor.edu/connections and you can subscribe to the program on iTunes. Thanks for joining us here on Baylor Connections.